- Home

- S. J. Morgan

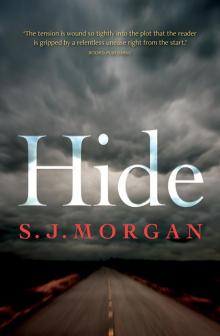

Hide

Hide Read online

First published 2019 by MidnightSun Publishing Pty Ltd

PO Box 3647, Rundle Mall, SA 5000, Australia.

www.midnightsunpublishing.com

Copyright © S.J. Morgan 2019

The moral rights of the author have been asserted.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted by any person or entity, including internet search engines or retailers (including, but not restricted to, Google and Amazon), in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying (except under the statutory exceptions provisions of the Australian Copyright Act 1968), recording, scanning or by any information storage and retrieval system without the prior written permission of MidnightSun Publishing.

Cover design by Kim Lock

Internal design by Zena Shapter

Typeset in American Typewriter and Garamond.

Printed and bound in Australia by Ovato. The papers used by MidnightSun in the manufacture of this book are natural, recyclable products made from wood grown in sustainable plantation forests.

For my precious butty-bachs: Robbi, Phoebe, Larne.

Chapter 1

December 1983 – Queensland/Northern Territory Border, Australia

The parched countryside shimmers as it stretches, purple-orange, into the distance. The track is only wide enough for a single vehicle but at this speed we won’t be the ones giving way. Not that there are any signs of life: since we turned off the main road, gnarled trunks have been our only company. The place is tinder-dry, wrung-out. Looks like every blade of grass is ready to blow. My T-shirt is heavy with sweat and it clings to my chest as I breathe.

It’s taken long enough but I finally spit it out: ‘Shouldn’t we get back on the highway?’

‘No, Alec. Not yet.’

My knee’s jiggling like a freaking jackhammer. ‘So, where are we going?’

When I get no response, I look over to him. Nothing. Just a blue vein pulsating along his leathery temple.

The question hangs there, swelling. Perspiration forms above my top lip.

Finally, he smiles; he fucking smiles at me. ‘Well, Alec,’ he says. ‘Let’s just call it...a detour.’

If I was watching this particular movie, I’d be thinking: ‘Why doesn’t he just open the truck door and fling himself out?’ or ‘Why doesn’t he put his hands around that asshole’s scrawny neck and squeeze?’ But no, I do nothing.

I’d barely got out my cardboard sign when he stopped to pick me up at first light.

‘Alice Springs?’ I’d said.

He gave a grunt and looked in his side mirror.

‘Okay?’

This time, I didn’t even get a grunt. He just leaned across, one bony-fingered hand on the steering wheel, the other pushing open the passenger door.

I put my bag in the footwell and buckled the seatbelt. ‘Alec,’ I said, holding out my hand.

He glanced down like I was offering him a fresh turd.

Checking his mirrors, he put on the indicator and took the main highway out of Mt Isa.

I put the turd back in my lap and focussed on the road signs. ‘Alice, one thousand, one hundred and seventy-two kilometres,’ I read aloud. ‘Should be there in an hour.’

My chauffeur slid his eyes towards me and didn’t crack a smile. ‘Zip it,’ he said. ‘I picked you up for one reason and one reason only. And it weren’t for your company.’

Chapter 2

Summer 1983 – Swansea, South Wales, UK

Bono was belting out ‘New Year’s Day’ from my speakers, his voice on a collision course with Van Halen upstairs. I sang along at the top of my lungs to give Bono a fighting chance. Stobes and me had this unspoken battle: every time one of us put a record on the turntable, so did the other. It was expected, like curry sauce with chips or a belch after a pint of dark. I always lost the sound battle, of course: Stobes had a half-decent set of speakers in his armoury whereas my fifty-quid pair of tins from Splott Market was never going to make any eardrums bleed.

Bono did manage to block out the doorbell though. The first I knew of visitors was when my bedroom door flew open and Black stumbled in. ‘You’re wanted downstairs, butty-bach,’ he yelled at me. ‘So, turn that shite off.’ He and his mop of black hair exited stage right while I turned off the hi-fi and went to the door.

I’d never exactly kept a welcome in the hillside for Mum and Dad, yet they seemed surprised by my expression when I met them on the doorstep.

‘You could at least pretend to be pleased,’ Mum said.

‘I am pleased! I just…wasn’t expecting you.’

‘So, this is the latest abode, is it?’ Mum’s gaze scuttled past me as she squinted through the dark hallway.

Trouble was, last time they’d seen me, I’d been moving into one of those neat, airy houses in the Hendrefoilan Student Village. House nine; my lucky number. A half-year down the track and it’d dawned on me that nine never had been that lucky. Me and uni were not happy bed mates, it turned out. And along with the student status, my grant money dried up and my housing options became more modest.

‘So, did you want to come in?’ I asked. I kept the door half-shut, ever the optimist.

‘We didn’t drive an hour from Cardiff to go straight home again,’ Mum said. And she wiped her feet, gave me a kiss and stepped inside.

Ours was one of the brooding, crumbling Victorian houses perched half-way up Constitution Hill, the steepest goddamn incline in the whole of Swansea. We could just about see The Vetch from my room and when City played at home, we got the full roar of the crowd.

None of us knew each other, not really. We’d all ended up there through friends of friends, I think. But for four guys who didn’t know one another from Adam, we got on pretty well. Maybe even got to like each other in a careless, couldn’t-give-a-shit kind of way.

The ground floor was out of bounds to us, so I shared the upstairs with a mouldy, sub-zero kitchen and Minto. He was a headcase was Minto, but he mostly kept himself to himself. If you managed the final, lung-sucking ascent to the top floor – which hardly anyone did – you’d find Stobes and Black: tucked away like a pair of grubs in their tiny attic rooms.

As for me, I’d managed to land myself the best room in the place – a huge space with two massive windows and crick-your-neck ceilings. There were no shelves, barely any sticks of furniture really, so all my abandoned college books were lined up, tight against the skirting board like soldiers on parade. The one rickety table I owned was dwarfed by the huge room, but it had just enough space for my twelve-inch telly.

As soon as I brought Mum and Dad through the hallway, I spotted the tell-tale flare of Mum’s nostrils. If she found the smell on the ground floor unpleasant, I figured she’d need a gas mask by the time she got to my room. Dad trailed behind us in his golf club blazer which he kept pressed and ready for weekend outings. I’d never imagined my place being on his list of must-see destinations but at least he’d made the effort. There seemed to be less of Dad lately. Where once he used to puff out his chest and stand tall and proud, now his body had reduced; sunk back on itself like he had a slow puncture.

As we started up the stairs, there was an almighty thud. Minto’s voice cut through the gloom above us: ‘Don’t you ever try that again, you little slut. Now piss off.’ There was a slap, then the slam of a door.

The three of us hovered, gripping the dodgy banister. ‘I’m sorry,’ I heard Sindy say. ‘I didn’t mean to. Please. Can I come back in?’

I was becoming used to this kind of thing. Since Sindy’d become a household feature, there was more drama at our place than there was on Dallas.

Mum was suddenly in front of me, heading up the stairs, two at a time.

‘Oh,’ I heard her say. ‘Oh, Lord. Are you all right, love

?’

By the time I caught up, Mum was crouched in front of Minto’s closed door. I couldn’t see anything of Sindy beside the outstretched stick of her leg.

‘Hurry up,’ Mum said to me, turning around. ‘Close your eyes! Go and get your duvet or something to put around her. Don’t look!’ She formed a makeshift barricade with her arms and stayed there, all lipstick and skirt suit, hunkered down on the threadbare carpet.

In my room, I was about to pick up my duvet but remembered Sindy’s body odour problem. Instead, I grabbed an old throw from the chair and chucked it in Mum’s direction.

‘Now, put this around you. You’re all right,’ she said. ‘No need to cry, love.’

Minto’s door opened and, as I ventured back into the hall, I was just in time to see Minto shove past Sindy before he tore down the stairs.

There was a ‘steady on’ from Dad just before the front door slammed.

‘Come on, love, let’s get you up,’ Mum said.

Sindy was in tears again. She looked like a Dickensian waif, all bundled up in that big old blanket, with her bare feet and her matted hair.

She was led into my room.

‘Have you got some clothes you don’t need, Alexander?’ Mum said. She looked around, ignoring the kick-ass view from my window. ‘Let’s get your young friend here dressed so we can go out, shall we?’ she said with a grimace. ‘I reckon we could all use some fresh air.’

Sindy was on the seat opposite me. My belt was pulled to its tightest, but the jeans still hung off her. And the short sleeves of my old Psychedelic Furs T-shirt reached halfway down her arms. The best I’d managed to find for her in the footwear department was a pair of flip-flops, five sizes too big. She’d hardly been able to walk in them, but Sindy was terminally accommodating.

I kept a close eye on the entrance as we huddled around the gingham-clothed table at the Copper Grill. It wasn’t at all how my day was meant to pan out and I knew if Minto found us with his loyal sidekick, I’d be looking for a new rental by nightfall.

Sindy had perked up like a pooch on pet pills. I’d never seen her looking as bright and attentive as she did right then, sitting there with a doughnut and a milkshake in front of her.

‘So, you don’t live at the house,’ Mum said, resting her forearms across the table.

‘No.’ Sindy stopped to take a bite from the doughnut. ‘But I spend most of my time there. Minto’s usually nice: he just has a bad temper. Also, I can be a really annoying person.’ She said this seriously, but when she saw our faces, she laughed and sprayed sugar crystals across her plate.

Mum glanced at me with a pinched look, as if all this was somehow my fault. Trouble is, Mum treats every kid like they’re porcelain. She hates any hint of neglect or abuse. I guess I could understand it: my little sister, Gina, died when she was three. One minute we thought she just had a cold – the next, it was lights-out. Meningitis. And people still say there’s a God.

‘I think you should stick with your friends who haven’t got such a bad temper, Sindy,’ Mum said, pouring herself some tea.

‘I haven’t got any other friends.’ Sindy wrapped her sugar-coated lips around the straw and swallowed.

‘If a young man treated my daughter like that,’ Dad piped up. ‘I’d knock him from here to kingdom come.’

We all blinked back at him. It was pretty much the first thing he’d said all day, but at least he sounded like he meant it.

Chapter 3

While the truck jostles and bumps along the ruts on the track, I sense us getting further from the highway. I look down, secretly watching my companion, trying to commit each snapshot to memory. Brown boots, small feet; canvas pants with a rip on the right knee; shit-green crew-neck jumper, washed too many times; loose thread on the hem, thinning at the elbows.

As I watch, he hooks an index finger along the neck of his sweater as if it’s suddenly too tight. A jumper in this heat: the guy must be roasting.

My eyes move down, to the hands on the steering wheel. Short nails, clean, well-managed; gold band on the fourth slender finger. Those hands look more suited to piano-playing than to truck driving. Or to kidnapping. There has to be a mistake.

‘How far are we from the next town?’ I ask. I watch his profile, waiting for some sign he’s heard me.

He has a sad look about him. His eyes are turned down at the corners as if they’re used to disappointment and those lips of his look like they’d need wrestling into a smile.

‘No idea,’ he says, turning to me at last. ‘But we ain’t there yet, that’s for sure.’

He watches – no, studies me – as if testing for a reaction.

‘You got no map then,’ I say.

He explodes a laugh. ‘No, Alec. No map.’

I glance down into my lap, then out the side window, trying to keep my voice light and steady. ‘You could drop me off here if it’s easier,’ I say.

He smiles to himself.

‘I can make my own way back to the main road.’

He looks me in the eye and keeps his gaze on me far longer than someone driving a truck should. ‘Why, Alec?’

‘I jus –’

‘There’s nothing wrong, is there?’ He rests his watery grey eyes on me.

‘No,’ I tell him. ‘I just...want to get there.’

He makes no reply and I sink back in my seat. My attention shifts to the wing mirror and I watch as we kick up a dust storm behind us and head for somewhere that I’m certain isn’t Alice.

Chapter 4

Until that day, I’d barely spoken to Sindy. When I first met her, I thought Minto was having a laugh – as did the others, by the looks on their faces. Minto stood in the kitchen doorway, his solid, leather-clad arm around this pale twig of a girl.

‘Sinds,’ he said, looking down at her. ‘Meet the gang. That’s Black over there. Stobie on the sofa and the ugly one there’s Alec.’ He lifted a finger from his can of ale to point in my direction and the others enjoyed a cackle at my expense. ‘And, before you ask, no, he’s not very smart.’ He was on a roll, was Minto. ‘And this is Sindy,’ he told us, squeezing her into a loose headlock.

Stobes was sprawled on the torn vinyl couch next to the cooker. He took his cigarette from his mouth, like he was doffing his cap for her. ‘All right?’ he said, in his cheery London accent. Then to the rest of us: ‘My sister used to have a doll called Sindy. You know, arch rival of Barbie. Bathtime Sindy, I think it was. Or was it Surfboard Sindy?’ He shifted his eyes back to Doorframe Sindy. ‘Which one are you, darlin’?’

Minto kissed the top of her head and whispered something in her ear. She left the room and I heard light steps on the squeaky floorboards in the hall.

The smile left Minto’s face as he looked back at Stobes. He jabbed a finger in his direction. ‘You watch your mouth,’ he said. ‘She’s mind-your-own-fucking-business Sindy as far as you’re concerned. Don’t you fucking forget it.’ His eyes slowly swept the room. ‘And that goes for the rest of you tossers.’

The door slammed and we all blinked at the empty spot Minto had left behind. There was a moment’s silence before there was a creak from the bed in Minto’s room.

‘Blow Job Sindy,’ Black said, sliding his eyes to Stobes.

They let out a triumphant whoop then nearly pissed themselves laughing.

She was certainly a change from Minto’s usual sort. If anything, Minto went for the older woman; usually buxom, too much make-up, mouthy. Not my type but at least I could see the attraction: these were women who knew what they were doing; who liked a good time and made sure you had one too. Sindy, though, she was one out of the box. She looked like she’d snap if she tried bending and I could see why Mum had wanted to feed her up; put some colour in her cheeks. Everything about Sindy screamed vulnerability.

She was friendly enough though, when you got her by herself, but she didn’t have a lot going on upstairs. Whenever she was around, I found myself speaking to her slowly, like she was a freaking dimwit

. ‘Half a bubble off plumb’ as Black liked to say.

I found her in the kitchen one morning, a few days after my folks had met her. She had a vest and pants on – and not the tantalising sort, either – a scuzzy old top and a pair of washed-too-often knickers. A bit like you’d expect to see on a kid of five. Or on Bathtime Sindy.

‘You all right?’ I said, putting on the kettle. ‘Not using this water, are you?’

‘No. I’m making toast.’ Bright, cheery voice she had, all whipped up with a singsong Swansea accent, but, Christ, she was nervous. She couldn’t speak without twisting a strand of hair or touching her face with those uncertain, skinny fingers of hers.

‘Did you and Minto go out last night?’ I asked. She made me uncomfortable, standing there, balancing one bare foot on the other.

‘No. We watched telly and then went to bed.’ Sindy rested her anxious blue eyes on me and smiled.

There was a metallic ‘ping’ from the toaster and Sindy reached past me. I took a step back, but she still managed to tread on my toe.

As usual, our shit-toaster wasn’t giving up the bread without a fight and Sindy took a knife from the drawer.

‘Hey, careful,’ I said, as she leaned over the toaster. ‘You can’t use metal.’

This is the result of my very practical upbringing. Such nuggets of useful information have been hot-wired into me from birth; like ‘Never Touch a Socket with Wet Hands’ or ‘Don’t put Damp Clothes on a Paraffin Heater.’

‘Use a wooden spoon,’ I said, going into the drawer.

As she stabbed it into the toaster, I turned off the switch at the wall. ‘Belt and braces, son. Belt and braces.’ Another gold nugget, right there.

Sindy placed the two slices of toast on the counter and smothered them in raspberry jam.

‘Got enough on there?’ I said.

She stood back, tilting her head this way and that like it was a Dali painting. ‘I think so.’

Hide

Hide